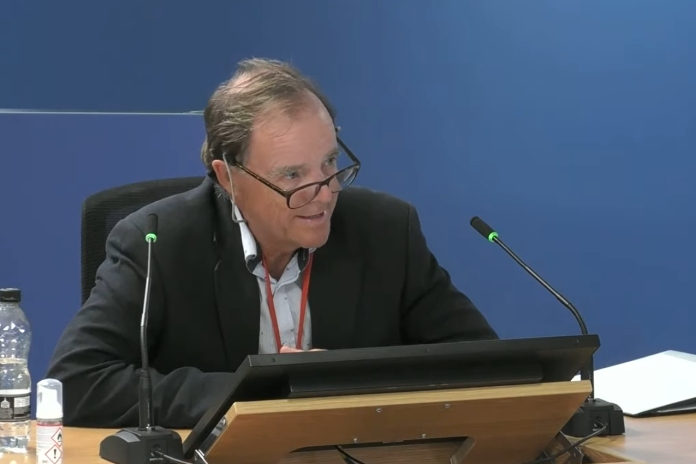

One of the clerks of works appointed to inspect work on the Grenfell Tower refurbishment has criticised the “mixed-up” way in which the construction industry now works, as he finished giving evidence to the Grenfell Tower Inquiry.

Jonathan White, who worked as a clerk of works for John Rowan and Partners from 2009, following a 26-year career with Mowlem, was in charge of inspecting general building works on the Grenfell Tower project.

He worked alongside Tony Batty, who inspected M&E works. They had been appointed by the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO), despite the fact that the TMO had not been obliged to do so under its design and build contract with Rydon.

White and Batty were appointed to work for a total of 80 days between them on the project, and began inspections in February 2015, around seven or eight months after the job started.

White hadn’t previously been involved in a job that involved ACM cladding or PIR insulation in a rainscreen cladding system, but said he was experienced with many other types of cladding over his career.

Confusion over the role

Despite being referred to regularly as a clerk of works, White insisted that he was actually a site inspector on Grenfell, who did not check for compliance, which he argued was the responsibility of Building Control.

Counsel to the Inquiry Rose Grogan asked White about KCTMO’s invitation to tender, which stated: “KCTMO requires an organisation to provide two clerks of works to assist in the supervision and monitoring of the works. One clerk of works should have experience in mechanical and electrical installations and the other with building works (ideally with experience of the installation of external cladding).”

Among the duties listed for the clerk of works was: “Being familiar with legal requirements and checking that the work complies with them.” Asked if had been told this would be one of his duties, White said: “Not specifically, but by checking that the legal requirements were fulfilled by other people, I would say that that’s what I did.”

He said he hadn’t familiarised himself with the requirements of Building Regulations as they would apply to an external rainscreen cladding system before starting his role because that wasn’t in his remit. He said that he wouldn’t have been equipped to note any non-compliances.

White claimed there was a “misunderstanding” about what his role was on the Grenfell Tower project. He said that while on previous projects he had acted as a clerk of works, working on site full time from the beginning to end of construction, his role at Grenfell was on of a site inspector or site monitor “because our role was far more limited in its scope and our overall involvement”.

Speaking to the Inquiry, he added: “It’s the confusion of the clerk of works and site inspector. I would always clarify that when we had a talk with the client, we would determine what our role was.”

Cladding inspection

White recalled how he went on the mast climbers of the building and would check what workers were doing on the cladding and where they were working. He said he would look to make sure everything was properly fitted and that there were no loose materials or any damage. He also recalled rejecting work on his first inspection of the cladding because the cladding was scratched and wasn’t presentable.

He described how, to check the work, he would go on the mast climber from the top of the building, checking work on each floor, down to the third floor, where a lot of the works had already been finished. Then he would move to the next climber, go all the way to the top, and start again.

However, he said he was never asked to inspect anything “specifically” before the cladding panels went on. However he did go up on the mast climbers to look at insulation and cavity barriers when he did his normal site inspections. He compiled 35 report in total, with 10 or 12 inspections conducted using the mast climbers. Asked if he ever recalled seeing drawings showing the location of cavity barriers within the cladding, White replied: “Not specifically, no.” He also answered that the location of the cavity barriers would not have been of interest because he didn’t see himself as having a role in design. Asked if he thought to check what had been specified in respect of the cladding, he answered: “No…I was only there one day a week so I had limited time and my role was not to check all the drawings or any of the specifications.”

Asked what he was looking for, he replied: “Generally that the work was neat and tidy, it wasn’t damaged, that everything seemed to be the same, it was all fitted with the same detail, there was no damage, and there were no holes insulation, the fixings were not loose. Generally I was just checking that there was nothing that stood out.”

He added: “I think because Building Control were regularly visiting and they were checking for compliance, if they had any issues then I would have looked at the cladding more.”

Asked about his impression of the works, he said: “It looked very neat, and when I first went up the mast climbers, I just observed what was going on, see if they were doing everything safely, and I spoke briefly to the men, they seemed very experienced, they’d done previous jobs with Rydons, rainscreen , this type of cladding, and they seemed very experienced, and what I noticed , what I saw — normally if a job looks neat and tidy, normally it’s a good way of thinking whether it’s been done properly.”

An ‘unhelpful presence’

Grogan asked White if he was aware that Rydon thought at times that the presence of the clerks of works was unhelpful.

White said: “I think our relationship early doors with Rydons was difficult because we came not at the beginning of the job, we weren’t part of the main team, we only started very late, and they weren’t keen for us to be there, and they didn’t really make us very welcome.”

But he said the relationship with the main contractor improved when Rydon’s final site manager, Dave Hughes, started. White said: “He understood that we were there to also help, and we had a much better relationship. So I’d say one team particularly didn’t want us to be there and weren’t particularly helpful, where Dave Hughes was very helpful and we tried to work together.”

At the end of the hearing, White asked Inquiry chair Sir Martin Moore-Bick if he could say something. He said: “I have two more years to retirement. I have been in this industry all my life. And I would just like to say, when I started this industry, all the responsibilities were clear. You had an architect who did the design, you had an M&E that did the design, a structural engineer that did all the calculations. The architect was the lead designer and he designed everything, and you had a builder to build. Now it’s all mixed up, and a builder is good at building, but a builder is not good at designing. I wish we could go back to what it was when I started.”

The Inquiry continues.

Comments

Comments are closed.

Back in the day, we operated a test and inspection (T&I) process whereby any work that was to be subsequently covered ( foundations, ground floor construction, drainage, first fix items etc) was inspected on site and only when it had passed inspection (and recorded as such) would the follow up work be completed.

As time went on however and prices and timescales became tighter this system was dropped as being too time consuming and expensive. Even when markets improved and Main Contractors were able to increase prices the T&I procedures were forgotten about and it was more about making as much money as you could when you could.

After 42 years in the industry, 20 as a manager, with regards the closing comment by Mr White I am in total agreement, its shambolic, CDM , HAHAHA, Principal Designer should always be an Architect surely.

I agree entirely with Mr. Whites final comments . Many contractors are now forced to tender for a range of design and build contracts of which they often have little or no understanding .

The use of design and build contracts, where the clients representatives look to pass on all responsibilities to the main contractor within an all embracing package, results in confusion and poor quality work.

The majority of project managers and site managers , rise up the ranks from trade bodies, often result in them managing without a full understanding of the full contractual requirements or responsibilities.

Ideally the Principal Designer should certainly be the architect. Unfortunately many refuse to accept the role (probably their insurers drive this) and the PD is often appointed just before work starts. Who is failing to give the client advice on the CDM regulations?

Mr Whites closing views tie in with my own previous submissions to CIOB Magazine. The comments mirror my own views already expressed regarding responsibility. Also I understood that the CDM Regulations were to improve the Construction Design and Management of Schemes. Design and Build Contracts have muddied the waters in what was at one time a simple process from Client, Architect, (Principal Designer) Building Control, through Main Contractor, and Clerk of Works and Building Inspector.

It certainly seems that things were as Mr White said mixed up. Were the CDM Regulations complied with? if so they are not fit for purpose – if not criminal charges are appropriate. Don’t forget many people list their lives.

Peter Anderson